Mickey 17: A Hauntological Response

Written By: Zackary Kozak

Published: August 5th, 2025

If I am haunted

Then you will see

– Opeth, Ghost Reveries, “Reveries / Harlequin Forest”

Bong Joon Ho’s latest film, Mickey 17, was released March 7th, and its final scene has haunted me ever since. There is something strikingly specific about Mickey’s final encounter with Ylfa:

In the middle of the night, Mickey finds Ylfa by the human printing machine. She urges him to take a “taste of faith” of her sauce (the “priceless delicacy”) before reprinting her husband, Kenneth Marshall. But then, Mickey remembers and refutes back to Ylfa, “You died, the day after Marshall.” Ylfa moves/floats/glides towards Mickey and responds, “Go ahead, touch me; see if I’m ghost or human.”

Is Mickey imagining this? Dreaming? Is he seeing Ylfa for the last time, or something different for the first time? Has Ylfa come back to haunt? This enigmatic sequence marks a spirit of Marx; a spirit that becomes a specter. The specter which Jacques Derrida spends Specters of Marx abstracting into reality (to put it imprecisely). The specter haunts Mickey, haunts this final scene: it haunts. I will utilize my reading of Derrida’s Specters of Marx to deconstruct the nature of this haunt and the spectral specificity of Mickey 17’s final scene. In doing so, I do not intend to privilege the economic or political as may be assumed by the aforementioned naming of Marx; however, I will privilege the philosophical over the film’s cinematic elegance and visual execution, which deserves an analysis in its own right.

How can a scene haunt? Be haunted? This ‘haunting’ is not the traditional spooky state of fear that may first come to mind, however, it is ghostly. It moves, floats, and glides as Ylfa so wickedly does. It is spectral. Let us now work with the specter more seriously:

Repetition and first time: this is perhaps the question of the event as question of the ghost. What is a ghost? What is the effectivity or the presence of a specter, that is, of what seems to remain as ineffective, virtual, insubstantial as a simulacrum? Is there there, between the thing itself and its simulacrum, an opposition that holds up? Repetition and first time, but also repetition and last time, since the singularity of any first time, makes of it also a last time. Each time it is the event itself, a first time is a last time. Altogether other. Staging for the end of history. Let us call it a hauntology. (Specters of Marx [SoM], 10)

Derrida’s specter is not easy to pin down. It seems to exist in instability, occupying a topology, stretching forward, backward, and in between a temporal space. This topological temporal space allows the specter to show itself to us in what could feel like both an occupation and suspension of time. As Derrida returns to constantly in his examination of specters and analysis of Hamlet: “The time is out of joint.” The specter seems to inhabit the absences, the gaps, the past-present, “here-now,” and future-present of temporality. It may appear for the first time but, in appearing, reappears – is seen once again, sees us once again.

Consider Mickey stumbling upon Ylfa in the final scene. He has certainly encountered her previously in the film – the all too memorable dinner with her and Kenneth Marshall (an important trauma to be touched on later) – but this is his first time encountering Ylfa posthumously. For hadn’t she died, recall, “the day after Marshall?” Mickey is now seen for the first time by an appearance of Ylfa that has come again, that has brought with it this temporal absence and presence: “Let us call it a hauntology.”

Nor does one see in flesh and blood this Thing that is not a thing, this thing that is invisible between its apparitions, when it reappears. This Thing meanwhile looks at us and sees us not see it even when it is there. A spectral asymmetry interrupts here all specularity. It de-synchronizes, it recalls us to anachrony. (SoM, 6)

The specter (“Thing”) hides in the topological timeline that I have traced just before. Instead of us rearranging the fold (the geometry) of this timeline, the specter reveals itself and sees us – surprising us with a twist of what we can see. This “spectral asymmetry” is vital to Mickey 17’s plot. Mickey’s life is pervaded by reappearance. Mickey is constantly under the pressure of both a previous and next life – filled with memories of the past and living with imminent death as his future. Where does Mickey’s life begin? And where does it end (if ever)? I use ‘where’ rather than ‘when’ to highlight Mickey’s existence on my topological object. If a knot were to be tied at one end of this object, the “spectral asymmetry” at play moves the knot to the other end, without notice; it forces us to reconsider time. Remember, Mickey is on his 17th repetition by the start of the film. As an Expendable, time, for Mickey, is kept by the enumerated iteration of his body. His memory, his consciousness has been and is stored in a “brick” which uploads into each subsequent body that Mickey inhabits.

Inhabits. There is this distance between body and soul. A distance, a repetition, an absence and a presence that “de-synchronizes” Mickey. In the final scene, it “recalls us to anachrony” by flashing back to Ylfa, who Mickey remembers to be dead. This flashback can also be seen as a flashforward to Mickey’s latest encounter with Ylfa; it might be best described as a warp, situating us in this specific moment where Ylfa disrupts Mickey. She is there in front of him, but her narrative weight is behind them. Mickey is caught in her gaze but she aberrates in and out of his own. The film’s non-chronology and dramatic diversity of tone emphasize this anachronic recollection. There is a feeling of unease. A sense that the scene is out of place, or better yet, “out of joint.” A specter emerges from the shadow. But how did it get there?

Amidst all of the bodies – freshly printed after every death – Mickey increasingly loses his corporeal autonomy. Mickey’s personality even changes between prints, and it is as if he has become a mere captain of delayed consciousness, lost in a sea of his own flesh. This loss of controlled corporeality is actualized by the birth of Mickey 18: the true doubling of bodies. Mickey must confront his desynchronization face-to-face. And here, the film cuts away to the past, to the past existing in the present, to the people of the fictional world debating the ethical and political ramifications of human printing and the case of multiples.

A set of transformations of all sorts (in particular, techno-scientifico-economico-media) exceeds both the traditional givens of the Marxist discourse and those of the liberal discourse opposed to it. Even if we have inherited some essential resources for projecting their analysis, we must first recognize that these mutations perturb the onto-theological schemas or the philosophies of technics as such. They disturb political philosophies and the common concepts of democracy, they oblige us to reconsider all relations between State and nation, man and citizen, the private and the public, and so forth. (SoM, 88)

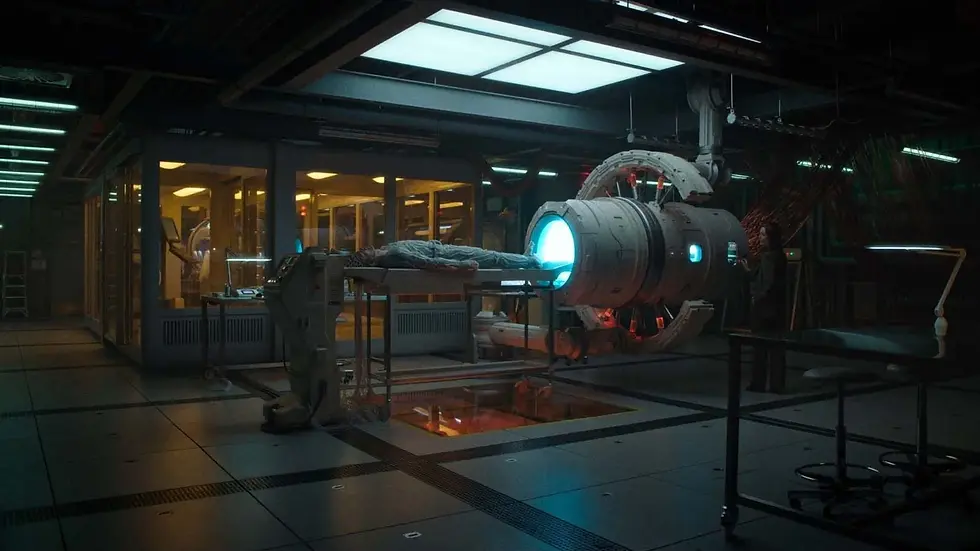

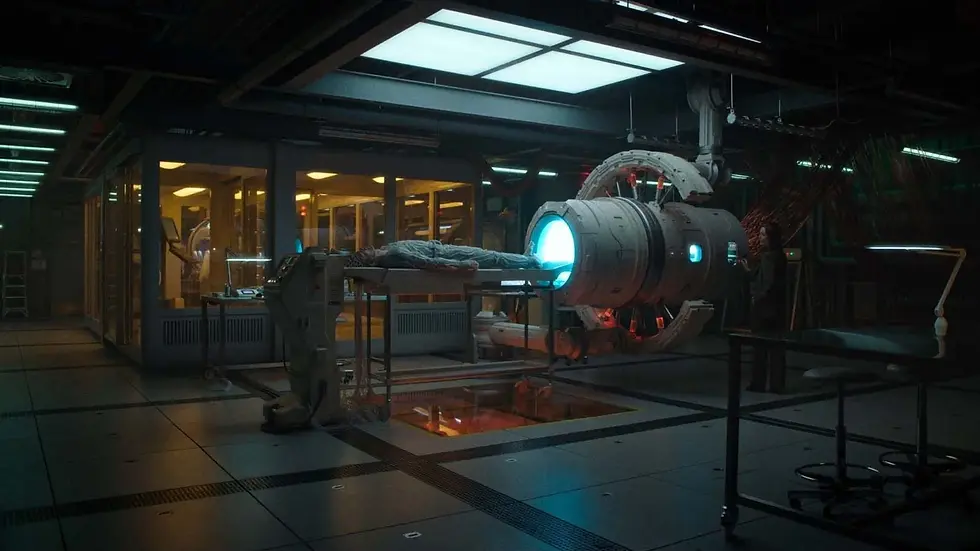

Derrida observes the power of certain advancements to transcend our current modes of explanation and, even if touching on elements we are familiar with (if it were material for Marxism or emancipating for liberalism), fracture the models we use to orient ourselves in society. Human printing is this particular “techno-scientifico-economico-media" that transcends the given discourse. It is the phantom elephant in the room, looming in the background of the Niflheim expedition. It waits as a flamethrower holds greater value than a fallen Mickey in the ice. Watches as Mickey is burned in the name of science. Rests beneath the screen as he almost spills blood on Ylfa’s Persian rug. The human printing machine is the bridge between relation and commodity. It masks the worth of Mickey’s efforts, and blurs the line between use-value and exchange-value.

This is where the film’s central economic throughline may bleed through. There is, at the very least, a question of value at hand. How does value change with the advent of human printing? What are the necessary costs of human progression? Of the ‘cosmocolonialism’ that Kenneth Marshall and Ylfa lead? For now, I’ll leave these questions unanswered, and choose to focus on what this “reconsider[ation] [of] all relations between State and nation, man and citizen, the private and the public, and so forth” means for Mickey.

Kenneth Marshall declares that “human printing is a sin” but a sin worth indulging nevertheless (a future analysis of the use of “sin” here as opposed to, or differed with, its use in Mickey and Timo’s macaron business – “Macarons Are Not A Sin” – may be rewarding). The technology is too promising not to be tested, so a fail-safe must be constructed. In the case of multiples, where a double of a body still alive has been printed, all will be executed; for there is comfort only with one soul, one body at a time. This conjuration of law begets the role of Expendable that Mickey Barnes assumes, and so begins the replacement of last name with number, sin with mission, birth with rebirth.

Hamlet is “out of joint” because he curses his own mission, the punishment that consists in having to punish, avenge, exercise justice and right in the form of reprisals; and what he curses in his mission is this expiation of expiation itself; it is first of all that it is inborn in him, given by his birth as much as at his birth…There is tragedy, there is essence of the tragic only on the condition of this originarity, more precisely of this pre-originary and properly spectral anteriority of the crime—the crime of the other, a misdeed whose event and reality, whose truth can never present themselves in flesh and blood, but can only allow themselves to be presumed, reconstructed, fantasized. (SoM, 23-24)

Does Mickey, like Hamlet, “curs[e] his own mission?” Is there a spectral crime? Well, by trusting Timo and taking out a massive loan for their presumably not massively successful macaron business, Mickey needed to escape. This escape leads to his new role as an Expendable and new mission that “is inborn in him, given by his birth as much as at his birth.” Mickey is born to die, not only born to die but born to endure whatever pain can be of use to the expedition. Eternal sacrifice. Mickey is permanently impermanent. What is culpable for this tragedy? The crime of Timo, the crime of Kenneth Marshall and Ylfa, the crime of Mickey himself “can never present themselves in flesh and blood, but can only allow themselves to be presumed, reconstructed, fantasized.” Without closure on these potentially spectral crimes, how can Mickey carry on?

Mourning always follows a trauma. I have tried to show elsewhere that the work of mourning is not one kind of work among others. It is work itself, work in general, the trait by means of which one ought perhaps to reconsider the very concept of production—in what links it to trauma, to mourning, to the idealizing iterability of exappropriation, thus to the spectral spiritualization that is at work in any tekhne. There is the temptation to add here an aporetic postscript to Freud’s remark that linked in a same comparative history three of the traumas inflicted on human narcissism when it is thus de-centered: the psychological trauma (the power of the unconscious over the conscious ego, discovered by psychoanalysis), after the biological trauma (the animal descent of man discovered by Darwin—to whom, moreover, Engels alludes in the Preface to the 1888 Manifesto), after the cosmological trauma (the Copernican Earth is no longer the center of the universe, and this is more and more the case one could say so as to draw from it many consequences concerning the limits of geopolitics). (SoM, 121)

To bring clarity to the previous questions of sin, culpability, and hope, we must dissect Mickey’s mourning and, necessarily, his multidimensional trauma. When Mickey becomes an Expendable, a lady with red hair explains the ins and outs of the position and administers the accompanying procedures. Mickey is captivated by the smell of her hair, experiencing a “déjà vu for a smell” – an olfactory absence and presence. The smell is of his mother’s hair. We then cut to a young Mickey held by his mother as they approach a car. Young Mickey hovers over a red button in the front seat as the narrating Mickey unfolds the guilt he feels for his mother’s death, apparently caused by the car accident. Is this Mickey’s originary sin? Or has the memory been haunted? Has the crime been “presumed, reconstructed, fantasized?”

No matter what, the guilt serves as evidence of Mickey's sustained psychological trauma – an unconscious blame put on himself. The brutal murder of one of Darius Blank’s borrowers serves as biological trauma – the chainsaw still churning in Mickey’s ears. This biological trauma is distorted and expanded by the life-death cycle that Mickey’s existence as an Expendable becomes. And finally, Mickey’s launch into outer space is the direct provocateur of cosmological trauma – the extraterrestrial physicalization of his alienation from others. Specters seem to infinitize these traumas throughout the film, but not without resistance from Mickey.

Mickey first finds solace in Nasha. Their companionship and sexual chemistry provides a catharsis from Mickey’s biological trauma. The addition of Mickey 18, however, complicates Nasha’s support. Mickey 18 inflames Mickey 17’s biological trauma; again, the doubling of bodies becomes burdensome. Furthermore, Nasha’s love begins to feel “out of joint.” Mickey 17 feels distanced by her infatuation with Mickey 18. It is as though she no longer loves just him but a separate other for their likeness – his own body that is not his own. Mickey 17’s valuable connection has been fetishized.

Recall Kai’s discovery that there are two Mickeys: she walks in on Nasha initiating a sexual encounter with both Mickey 17 and Mickey 18 simultaneously. In an effort to salve the situation, Kai attempts to negotiate with Nasha, requesting to share Mickey – 17 for Kai, 18 for Nasha. Nasha brazenly refuses:

“Mickey is not some cookie you can split in half. 17 and 18 are both Mickey. Both my Mickey.”

Mickey 17 and 18 are separately inseparable. They are each other's other. An altogether othering that will eventually enjoin expiation. (Interestingly, there is an emphasis of possession in Nasha’s tone: “my.” Is Mickey like a commodity? How are the lines of social relation drawn? What exactly is Nasha’s to possess? This complex dynamic between Nasha and Mickey (or the Mickeys, 17 and 18) remains unstable).

While Nasha and Kai negotiate, Mickey 18 rages at Mickey 17 as they discuss another biological trauma: ‘the dinner event’ (hinted at earlier in this article) where Kenneth Marshall almost shoots Mickey 17 in the head until Ylfa prevents him from spilling blood on her precious Persian rug. On the surface, this confrontation between Mickey 18 and Mickey 17 advances the plot, inciting Mickey 18’s assassination attempt on Kenneth Marshall and bringing our attention to the native creatures of Niflheim (to be discussed momentarily). By digging deeper, we uncover an interesting absence and presence. Mickey 18’s aggressive call for clarification, with regard to the dinner event, reminds us that there are gaps in the memory of Mickey; in other words, Mickey 17’s memories since the birth of Mickey 18 are solely his own – another upload has yet to occur. Yet the past still connects them. Mickey 18, in a pause from infuriation, says to Mickey 17:

“It’s not your fault.”

This somewhat inconspicuous line lies at the foundation of Mickey 17’s search for stability. What is Mickey not at fault for? It is unlikely that Mickey 18 is referring to the dinner event they have just fought over (he is passionate that Mickey 17 is wrong for how he failed to act against Kenneth Marshall) , or anything else we have seen Mickey 17 do on-screen; remember, there are gaps in the most recent memories. The expiating invocation – “It’s not your fault” – delivered after a deep breath is about Mickey’s mother: it is not Mickey 17’s fault that his mother died in that psychologically traumatic car accident. Intriguingly, Mickey 18 distances himself from this grief with the use of “your.” Mickey 18 does not say “It’s not our fault;” he chooses “your.” It appears that Mickey 18, unlike Mickey 17, has mourned.

Mickey 17 is not quite there yet. With Mickey 18’s wild attack on Kenneth Marshall gone awry, a “Creeper” – the name given by Ylfa and Kenneth Marshall to the native creatures of Niflheim – is killed. This initiates a conflict (between the people of the expedition and the Creepers) which Mickey 17 is uniquely positioned to reconcile. After Mickey 17’s fall into the ravine of ice that begins the film, it is not Timo that saves him but a group of Creepers. Initially, Mickey 17 thought nothing of this, but it leads himself, Nasha, and Dorothy (one of the scientists aboard) to recognize the complexity of these creatures and develop a translation device that facilitates communication between humans and Creepers. To quickly summarize: Mickey 17 communicates the Creepers’ demands, Nasha saves a Creeper held hostage, and Mickey 18 sacrifices himself to kill Kenneth Marshall, thus carrying out the Creepers’ requirements for peace.

Six months later and it is spring – a classic symbol of birth and rebirth. Mickey 17 has fostered a relationship with the Creepers, and their reconciliation seems to have helped heal some cosmological trauma, bringing him closer to a shared sense of space. Mickey 18’s death has also brought back some of Mickey 17’s lost corporeality, healing the biological trauma that had been aggravated as of late. And now we have returned to the final scene, to the Niflheim groundbreaking ceremony, to the abolishment of the Expendables program, to Ylfa’s haunt.

Mickey 17 has reclaimed his last name and is once again Mickey Barnes. He is presented with a red button which will explode the human printing machine and end the Expendables program. In the moment before he presses the button, Ylfa utters that fateful request:

“Go ahead, touch me; see if I’m ghost or human.”

Mickey Barnes conjures Mickey 18 – “I just thought to myself, what would 18 do?” – and responds: “Fuck off.”

We cut back to Mickey at the ceremony: he pushes the button, blows past the psychological trauma represented by the red button of his mother’s car crash, and is now, as fully as ever, Mickey Barnes.

A question of repetition: a specter is always a revenant. One cannot control its comings and goings because it begins by coming back. (SoM, 11)

It is a proper characteristic of the specter, if there is any, that no one can be sure if by returning it testifies to a living past or to a living future, for the revenant may already mark the promised return of the specter of living being. (SoM, 123)

So, does a specter attest “to a living past or to a living future?” Has Mickey Barnes internalized his trauma? Properly mourned? It is safe to say that Mickey is on his way: his guilt lingers but dwindles. There is still much else to decipher. Is the reprinting of Kenneth Marshall in the final scene truly "what everyone wants?” Will his ideology live on? Is there more to Ylfa’s sauce, or is it a taste of exploitation, a commodity “out of joint?” What are the implications of Niflheim’s etymology – the Norse primordial realm of the dead? Is there hope? To the latter, I say yes.

Although I have left a lot unanswered, I hope that this investigation has opened up the film’s underlying spectrality. It is this exploratory potential that has me returning to Bong Joon Ho’s filmography and praising the craftsmanship that goes into these wonderful works of art. The short quotes from Jacques Derrida’s Specters of Marx do not give justice to the original text (which even I read via the mediation of translation), however, with luck they inspired curiosity into his philosophy and inception of spectrality. I will leave it to you, the reader, to fill in the gaps of my own text and to see, to feel whether you have been haunted as well.

*Peggy Kamuf’s translation of Specters of Marx was used in this article.

If I am haunted

Then you will see

– Opeth, Ghost Reveries, “Reveries / Harlequin Forest”

Bong Joon Ho’s latest film, Mickey 17, was released March 7th, and its final scene has haunted me ever since. There is something strikingly specific about Mickey’s final encounter with Ylfa:

In the middle of the night, Mickey finds Ylfa by the human printing machine. She urges him to take a “taste of faith” of her sauce (the “priceless delicacy”) before reprinting her husband, Kenneth Marshall. But then, Mickey remembers and refutes back to Ylfa, “You died, the day after Marshall.” Ylfa moves/floats/glides towards Mickey and responds, “Go ahead, touch me; see if I’m ghost or human.”

Is Mickey imagining this? Dreaming? Is he seeing Ylfa for the last time, or something different for the first time? Has Ylfa come back to haunt? This enigmatic sequence marks a spirit of Marx; a spirit that becomes a specter. The specter which Jacques Derrida spends Specters of Marx abstracting into reality (to put it imprecisely). The specter haunts Mickey, haunts this final scene: it haunts. I will utilize my reading of Derrida’s Specters of Marx to deconstruct the nature of this haunt and the spectral specificity of Mickey 17’s final scene. In doing so, I do not intend to privilege the economic or political as may be assumed by the aforementioned naming of Marx; however, I will privilege the philosophical over the film’s cinematic elegance and visual execution, which deserves an analysis in its own right.

How can a scene haunt? Be haunted? This ‘haunting’ is not the traditional spooky state of fear that may first come to mind, however, it is ghostly. It moves, floats, and glides as Ylfa so wickedly does. It is spectral. Let us now work with the specter more seriously:

Repetition and first time: this is perhaps the question of the event as question of the ghost. What is a ghost? What is the effectivity or the presence of a specter, that is, of what seems to remain as ineffective, virtual, insubstantial as a simulacrum? Is there there, between the thing itself and its simulacrum, an opposition that holds up? Repetition and first time, but also repetition and last time, since the singularity of any first time, makes of it also a last time. Each time it is the event itself, a first time is a last time. Altogether other. Staging for the end of history. Let us call it a hauntology. (Specters of Marx [SoM], 10)

Derrida’s specter is not easy to pin down. It seems to exist in instability, occupying a topology, stretching forward, backward, and in between a temporal space. This topological temporal space allows the specter to show itself to us in what could feel like both an occupation and suspension of time. As Derrida returns to constantly in his examination of specters and analysis of Hamlet: “The time is out of joint.” The specter seems to inhabit the absences, the gaps, the past-present, “here-now,” and future-present of temporality. It may appear for the first time but, in appearing, reappears – is seen once again, sees us once again.

Consider Mickey stumbling upon Ylfa in the final scene. He has certainly encountered her previously in the film – the all too memorable dinner with her and Kenneth Marshall (an important trauma to be touched on later) – but this is his first time encountering Ylfa posthumously. For hadn’t she died, recall, “the day after Marshall?” Mickey is now seen for the first time by an appearance of Ylfa that has come again, that has brought with it this temporal absence and presence: “Let us call it a hauntology.”

Nor does one see in flesh and blood this Thing that is not a thing, this thing that is invisible between its apparitions, when it reappears. This Thing meanwhile looks at us and sees us not see it even when it is there. A spectral asymmetry interrupts here all specularity. It de-synchronizes, it recalls us to anachrony. (SoM, 6)

The specter (“Thing”) hides in the topological timeline that I have traced just before. Instead of us rearranging the fold (the geometry) of this timeline, the specter reveals itself and sees us – surprising us with a twist of what we can see. This “spectral asymmetry” is vital to Mickey 17’s plot. Mickey’s life is pervaded by reappearance. Mickey is constantly under the pressure of both a previous and next life – filled with memories of the past and living with imminent death as his future. Where does Mickey’s life begin? And where does it end (if ever)? I use ‘where’ rather than ‘when’ to highlight Mickey’s existence on my topological object. If a knot were to be tied at one end of this object, the “spectral asymmetry” at play moves the knot to the other end, without notice; it forces us to reconsider time. Remember, Mickey is on his 17th repetition by the start of the film. As an Expendable, time, for Mickey, is kept by the enumerated iteration of his body. His memory, his consciousness has been and is stored in a “brick” which uploads into each subsequent body that Mickey inhabits.

Inhabits. There is this distance between body and soul. A distance, a repetition, an absence and a presence that “de-synchronizes” Mickey. In the final scene, it “recalls us to anachrony” by flashing back to Ylfa, who Mickey remembers to be dead. This flashback can also be seen as a flashforward to Mickey’s latest encounter with Ylfa; it might be best described as a warp, situating us in this specific moment where Ylfa disrupts Mickey. She is there in front of him, but her narrative weight is behind them. Mickey is caught in her gaze but she aberrates in and out of his own. The film’s non-chronology and dramatic diversity of tone emphasize this anachronic recollection. There is a feeling of unease. A sense that the scene is out of place, or better yet, “out of joint.” A specter emerges from the shadow. But how did it get there?

Amidst all of the bodies – freshly printed after every death – Mickey increasingly loses his corporeal autonomy. Mickey’s personality even changes between prints, and it is as if he has become a mere captain of delayed consciousness, lost in a sea of his own flesh. This loss of controlled corporeality is actualized by the birth of Mickey 18: the true doubling of bodies. Mickey must confront his desynchronization face-to-face. And here, the film cuts away to the past, to the past existing in the present, to the people of the fictional world debating the ethical and political ramifications of human printing and the case of multiples.

A set of transformations of all sorts (in particular, techno-scientifico-economico-media) exceeds both the traditional givens of the Marxist discourse and those of the liberal discourse opposed to it. Even if we have inherited some essential resources for projecting their analysis, we must first recognize that these mutations perturb the onto-theological schemas or the philosophies of technics as such. They disturb political philosophies and the common concepts of democracy, they oblige us to reconsider all relations between State and nation, man and citizen, the private and the public, and so forth. (SoM, 88)

Derrida observes the power of certain advancements to transcend our current modes of explanation and, even if touching on elements we are familiar with (if it were material for Marxism or emancipating for liberalism), fracture the models we use to orient ourselves in society. Human printing is this particular “techno-scientifico-economico-media" that transcends the given discourse. It is the phantom elephant in the room, looming in the background of the Niflheim expedition. It waits as a flamethrower holds greater value than a fallen Mickey in the ice. Watches as Mickey is burned in the name of science. Rests beneath the screen as he almost spills blood on Ylfa’s Persian rug. The human printing machine is the bridge between relation and commodity. It masks the worth of Mickey’s efforts, and blurs the line between use-value and exchange-value.

This is where the film’s central economic throughline may bleed through. There is, at the very least, a question of value at hand. How does value change with the advent of human printing? What are the necessary costs of human progression? Of the ‘cosmocolonialism’ that Kenneth Marshall and Ylfa lead? For now, I’ll leave these questions unanswered, and choose to focus on what this “reconsider[ation] [of] all relations between State and nation, man and citizen, the private and the public, and so forth” means for Mickey.

Kenneth Marshall declares that “human printing is a sin” but a sin worth indulging nevertheless (a future analysis of the use of “sin” here as opposed to, or differed with, its use in Mickey and Timo’s macaron business – “Macarons Are Not A Sin” – may be rewarding). The technology is too promising not to be tested, so a fail-safe must be constructed. In the case of multiples, where a double of a body still alive has been printed, all will be executed; for there is comfort only with one soul, one body at a time. This conjuration of law begets the role of Expendable that Mickey Barnes assumes, and so begins the replacement of last name with number, sin with mission, birth with rebirth.

Hamlet is “out of joint” because he curses his own mission, the punishment that consists in having to punish, avenge, exercise justice and right in the form of reprisals; and what he curses in his mission is this expiation of expiation itself; it is first of all that it is inborn in him, given by his birth as much as at his birth…There is tragedy, there is essence of the tragic only on the condition of this originarity, more precisely of this pre-originary and properly spectral anteriority of the crime—the crime of the other, a misdeed whose event and reality, whose truth can never present themselves in flesh and blood, but can only allow themselves to be presumed, reconstructed, fantasized. (SoM, 23-24)

Does Mickey, like Hamlet, “curs[e] his own mission?” Is there a spectral crime? Well, by trusting Timo and taking out a massive loan for their presumably not massively successful macaron business, Mickey needed to escape. This escape leads to his new role as an Expendable and new mission that “is inborn in him, given by his birth as much as at his birth.” Mickey is born to die, not only born to die but born to endure whatever pain can be of use to the expedition. Eternal sacrifice. Mickey is permanently impermanent. What is culpable for this tragedy? The crime of Timo, the crime of Kenneth Marshall and Ylfa, the crime of Mickey himself “can never present themselves in flesh and blood, but can only allow themselves to be presumed, reconstructed, fantasized.” Without closure on these potentially spectral crimes, how can Mickey carry on?

Mourning always follows a trauma. I have tried to show elsewhere that the work of mourning is not one kind of work among others. It is work itself, work in general, the trait by means of which one ought perhaps to reconsider the very concept of production—in what links it to trauma, to mourning, to the idealizing iterability of exappropriation, thus to the spectral spiritualization that is at work in any tekhne. There is the temptation to add here an aporetic postscript to Freud’s remark that linked in a same comparative history three of the traumas inflicted on human narcissism when it is thus de-centered: the psychological trauma (the power of the unconscious over the conscious ego, discovered by psychoanalysis), after the biological trauma (the animal descent of man discovered by Darwin—to whom, moreover, Engels alludes in the Preface to the 1888 Manifesto), after the cosmological trauma (the Copernican Earth is no longer the center of the universe, and this is more and more the case one could say so as to draw from it many consequences concerning the limits of geopolitics). (SoM, 121)

To bring clarity to the previous questions of sin, culpability, and hope, we must dissect Mickey’s mourning and, necessarily, his multidimensional trauma. When Mickey becomes an Expendable, a lady with red hair explains the ins and outs of the position and administers the accompanying procedures. Mickey is captivated by the smell of her hair, experiencing a “déjà vu for a smell” – an olfactory absence and presence. The smell is of his mother’s hair. We then cut to a young Mickey held by his mother as they approach a car. Young Mickey hovers over a red button in the front seat as the narrating Mickey unfolds the guilt he feels for his mother’s death, apparently caused by the car accident. Is this Mickey’s originary sin? Or has the memory been haunted? Has the crime been “presumed, reconstructed, fantasized?”

No matter what, the guilt serves as evidence of Mickey's sustained psychological trauma – an unconscious blame put on himself. The brutal murder of one of Darius Blank’s borrowers serves as biological trauma – the chainsaw still churning in Mickey’s ears. This biological trauma is distorted and expanded by the life-death cycle that Mickey’s existence as an Expendable becomes. And finally, Mickey’s launch into outer space is the direct provocateur of cosmological trauma – the extraterrestrial physicalization of his alienation from others. Specters seem to infinitize these traumas throughout the film, but not without resistance from Mickey.

Mickey first finds solace in Nasha. Their companionship and sexual chemistry provides a catharsis from Mickey’s biological trauma. The addition of Mickey 18, however, complicates Nasha’s support. Mickey 18 inflames Mickey 17’s biological trauma; again, the doubling of bodies becomes burdensome. Furthermore, Nasha’s love begins to feel “out of joint.” Mickey 17 feels distanced by her infatuation with Mickey 18. It is as though she no longer loves just him but a separate other for their likeness – his own body that is not his own. Mickey 17’s valuable connection has been fetishized.

Recall Kai’s discovery that there are two Mickeys: she walks in on Nasha initiating a sexual encounter with both Mickey 17 and Mickey 18 simultaneously. In an effort to salve the situation, Kai attempts to negotiate with Nasha, requesting to share Mickey – 17 for Kai, 18 for Nasha. Nasha brazenly refuses:

“Mickey is not some cookie you can split in half. 17 and 18 are both Mickey. Both my Mickey.”

Mickey 17 and 18 are separately inseparable. They are each other's other. An altogether othering that will eventually enjoin expiation. (Interestingly, there is an emphasis of possession in Nasha’s tone: “my.” Is Mickey like a commodity? How are the lines of social relation drawn? What exactly is Nasha’s to possess? This complex dynamic between Nasha and Mickey (or the Mickeys, 17 and 18) remains unstable).

While Nasha and Kai negotiate, Mickey 18 rages at Mickey 17 as they discuss another biological trauma: ‘the dinner event’ (hinted at earlier in this article) where Kenneth Marshall almost shoots Mickey 17 in the head until Ylfa prevents him from spilling blood on her precious Persian rug. On the surface, this confrontation between Mickey 18 and Mickey 17 advances the plot, inciting Mickey 18’s assassination attempt on Kenneth Marshall and bringing our attention to the native creatures of Niflheim (to be discussed momentarily). By digging deeper, we uncover an interesting absence and presence. Mickey 18’s aggressive call for clarification, with regard to the dinner event, reminds us that there are gaps in the memory of Mickey; in other words, Mickey 17’s memories since the birth of Mickey 18 are solely his own – another upload has yet to occur. Yet the past still connects them. Mickey 18, in a pause from infuriation, says to Mickey 17:

“It’s not your fault.”

This somewhat inconspicuous line lies at the foundation of Mickey 17’s search for stability. What is Mickey not at fault for? It is unlikely that Mickey 18 is referring to the dinner event they have just fought over (he is passionate that Mickey 17 is wrong for how he failed to act against Kenneth Marshall) , or anything else we have seen Mickey 17 do on-screen; remember, there are gaps in the most recent memories. The expiating invocation – “It’s not your fault” – delivered after a deep breath is about Mickey’s mother: it is not Mickey 17’s fault that his mother died in that psychologically traumatic car accident. Intriguingly, Mickey 18 distances himself from this grief with the use of “your.” Mickey 18 does not say “It’s not our fault;” he chooses “your.” It appears that Mickey 18, unlike Mickey 17, has mourned.

Mickey 17 is not quite there yet. With Mickey 18’s wild attack on Kenneth Marshall gone awry, a “Creeper” – the name given by Ylfa and Kenneth Marshall to the native creatures of Niflheim – is killed. This initiates a conflict (between the people of the expedition and the Creepers) which Mickey 17 is uniquely positioned to reconcile. After Mickey 17’s fall into the ravine of ice that begins the film, it is not Timo that saves him but a group of Creepers. Initially, Mickey 17 thought nothing of this, but it leads himself, Nasha, and Dorothy (one of the scientists aboard) to recognize the complexity of these creatures and develop a translation device that facilitates communication between humans and Creepers. To quickly summarize: Mickey 17 communicates the Creepers’ demands, Nasha saves a Creeper held hostage, and Mickey 18 sacrifices himself to kill Kenneth Marshall, thus carrying out the Creepers’ requirements for peace.

Six months later and it is spring – a classic symbol of birth and rebirth. Mickey 17 has fostered a relationship with the Creepers, and their reconciliation seems to have helped heal some cosmological trauma, bringing him closer to a shared sense of space. Mickey 18’s death has also brought back some of Mickey 17’s lost corporeality, healing the biological trauma that had been aggravated as of late. And now we have returned to the final scene, to the Niflheim groundbreaking ceremony, to the abolishment of the Expendables program, to Ylfa’s haunt.

Mickey 17 has reclaimed his last name and is once again Mickey Barnes. He is presented with a red button which will explode the human printing machine and end the Expendables program. In the moment before he presses the button, Ylfa utters that fateful request:

“Go ahead, touch me; see if I’m ghost or human.”

Mickey Barnes conjures Mickey 18 – “I just thought to myself, what would 18 do?” – and responds: “Fuck off.”

We cut back to Mickey at the ceremony: he pushes the button, blows past the psychological trauma represented by the red button of his mother’s car crash, and is now, as fully as ever, Mickey Barnes.

A question of repetition: a specter is always a revenant. One cannot control its comings and goings because it begins by coming back. (SoM, 11)

It is a proper characteristic of the specter, if there is any, that no one can be sure if by returning it testifies to a living past or to a living future, for the revenant may already mark the promised return of the specter of living being. (SoM, 123)

So, does a specter attest “to a living past or to a living future?” Has Mickey Barnes internalized his trauma? Properly mourned? It is safe to say that Mickey is on his way: his guilt lingers but dwindles. There is still much else to decipher. Is the reprinting of Kenneth Marshall in the final scene truly "what everyone wants?” Will his ideology live on? Is there more to Ylfa’s sauce, or is it a taste of exploitation, a commodity “out of joint?” What are the implications of Niflheim’s etymology – the Norse primordial realm of the dead? Is there hope? To the latter, I say yes.

Although I have left a lot unanswered, I hope that this investigation has opened up the film’s underlying spectrality. It is this exploratory potential that has me returning to Bong Joon Ho’s filmography and praising the craftsmanship that goes into these wonderful works of art. The short quotes from Jacques Derrida’s Specters of Marx do not give justice to the original text (which even I read via the mediation of translation), however, with luck they inspired curiosity into his philosophy and inception of spectrality. I will leave it to you, the reader, to fill in the gaps of my own text and to see, to feel whether you have been haunted as well.

*Peggy Kamuf’s translation of Specters of Marx was used in this article.

Mickey 17: A Hauntological Response

Written By: Zackary Kozak

Published: August 5th, 2025